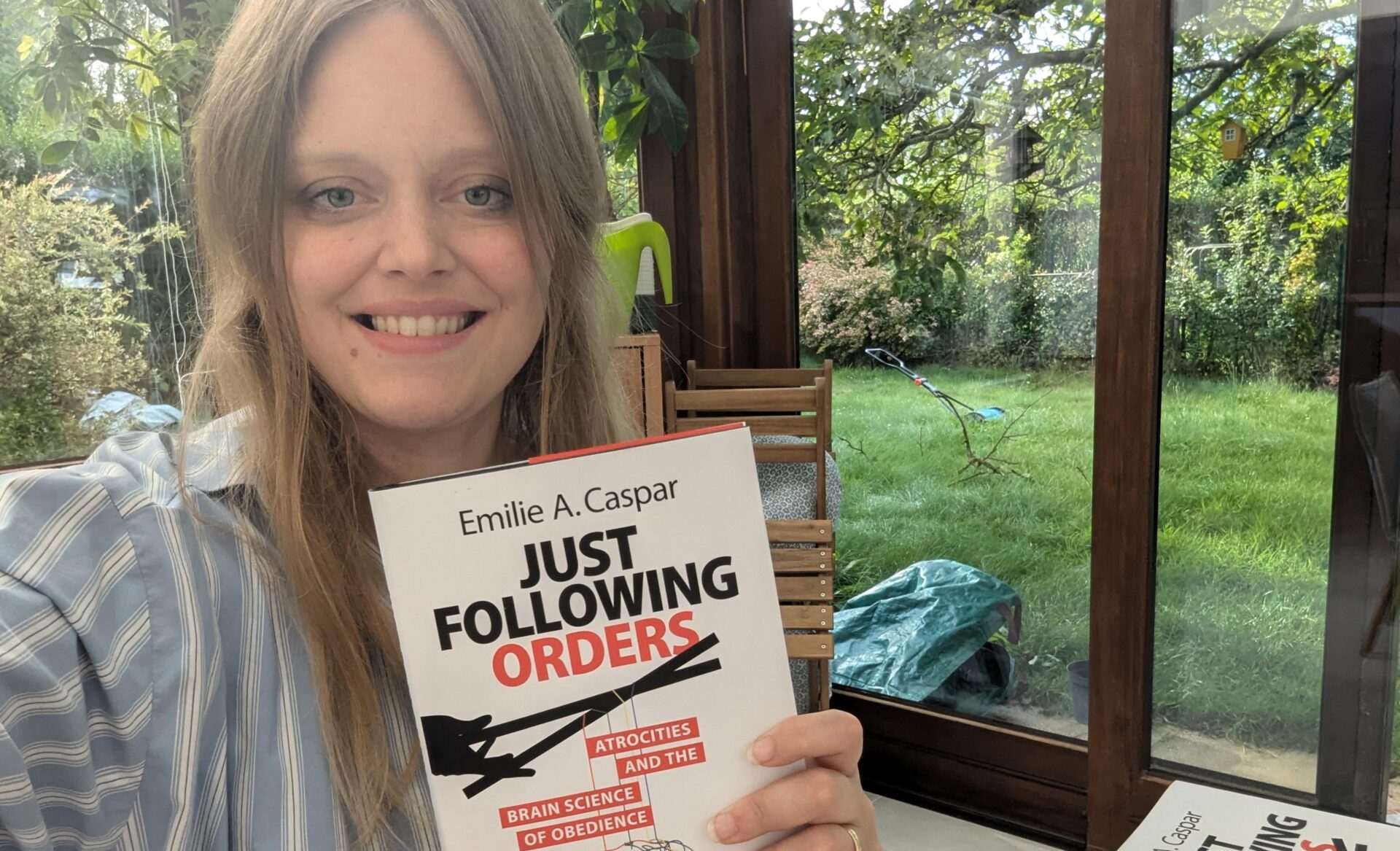

Emilie Caspar, former PhD student and postdoc at the CRCN with Axel Cleeremans, has just published her book Just Following Orders: Atrocities and the Brain Science of Obedience with Cambridge University Press. In this book intended for a general audience Emilie addresses a fundamental societal and scientific question: How can people commit atrocities when they follow orders?

During the Holocaust, for example, the Nazi leadership established a meticulously organized bureaucratic system through which orders to commit atrocities were disseminated. Lower-ranking individuals could rationalize their actions by claiming they were simply following orders. Similarly, under Pol Pot’s leadership, the Khmer Rouge enforced a strict social hierarchy. This hierarchical division reduced direct accountability and led individuals to believe they were working toward a higher collective goal, thereby enabling the widespread perpetration of genocide. How can this diffusion of responsibility be so powerful that, when we receive orders, we seem to forget our basic human moral values? How have several regimes been able to implement this diffusion of responsibility on such a massive scale, with only a small percentage of the population resisting and organizing rescue efforts instead?

Addressing this question is at the core of Emilie’s research. She uses methods from neuroscience and cognitive psychology in a field of research that was previously only by social psychologists, most notably through the (in)famous studies of Stanley Milgram. In her book, she explains how the brain processes our sense of agency and responsibility for our actions, our empathy when witnessing someone in pain, and our feelings of guilt following actions that harm another. She details experimental approaches using various neuroscience methods to show how these processes are altered when individuals obey orders to inflict pain, compared to when they act freely.

After several years of research using methods of neuroscience, she realized that fully capturing the complexity of obedience required a more direct approach. Despite being a neuroscientist accustomed to the confines of university offices and experimental rooms, she took an unusual step for the field: She ventured out with portable electroencephalograms and an audio recorder to meet former genocide perpetrators in Rwanda and Cambodia, who were still alive and had been released from prison. She also complemented her usual research with a qualitative approach and analyzed their narratives, which she also presents in the book. These stories serve not only to illustrate the raw complexities of obedience and resistance but also to offer a lens through which we can reevaluate our understanding of human behavior.

The book retraces also the human adventure of Emilie’s journey as a researcher. Convincing supervisors, colleagues and funding agencies to that conducting neuroscience in rural parts of the world – often neglected by scientists – and meeting with genocide perpetrators and rescuers was not without its obstacles. Thanks to initial funding for her FNRS fellowship, she conducted a first study in Rwanda, and then a second one. Now, she supervises a full Ph.D. student there and is trying to create a completely new track in neuropsychology. Emilie explains how difficult those research projects were, but also shows that stepping outside the comfort of university labs to extend the research populations is crucial. Neuroscientists have focused too much on a small portion of the world’s population to draw conclusions about the human brain, ignoring how culture and the environment shape cognitive functions. With this book, she aims to prove that such projects are feasible and worth the effort.

The book has been released worldwide and has been available since September 12th, and can be ordered in your favourite bookstore or directly here.